Richard Lang: #6 Rebel Leader

The Life and Times of Richard Lang (1744-1817), His Family and Other Related Matters

Much of what I know about Richard Lang and his family comes from secondary sources which is not ideal. Both information and evidence are incomplete in places.

This post is the sixth in a series of posts about Richard Lang, his family and other related matters. If you would like to read from the beginning, you can find Part #1 here:

A Brief catch-Up

By the 1790’s, many of the immigrants to Spanish East Florida, including Richard Lang were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of commercial and political freedom in Spanish East Florida. There were severe trade restrictions with the United States. This prompted illegal trading (Part #4).

For some people, this dissatisfaction led them to collude with French agents and the United States in a planned invasion of Spanish East Florida. For others, their dissatisfaction simmered along until two key events, prompted by the threat of invasion, really ‘tipped the scales’ and left many people feeling aggrieved (Part #5).

These events of 1794 were:

The arrest and imprisonment, under harsh conditions and without trial, of some of the men and, in particular, the arbitrary nature of some of those arrests on the basis of hearsay and innuendo, including that of Richard Lang; and

The emergency measures taken by the Spanish while the men were imprisoned resulting in the loss of their property and the displacement of their families, and other settler families.

Richard’s loyalty to the Spanish was severely tested by these two events, as was the loyalty of several other men of Anglo-American origin who had settled in Spanish East Florida with their families.

Disaffection without redress prompted rebellion.

East Florida Rebellion (1795)

Richard Lang, John Mcintosh, John Peter Wagnon, William Plowden, and William Jones (all of whom were amongst those who had been arrested in 1794) instigated, and led, the East Florida Rebellion of 17951.

This action had been encouraged by the French who, it seems, were quick to capitalise on the situation. Immediately prior to the rebellion, a French consular agent had been:

'fanning the smouldering discontent of Anglo-Spanish settlers between the Saint John and Saint Marys River; he let it be known that France was willing to underwrite an uprising with powerful aid'2

.

A Short-lived Campaign

The East Florida Rebellion began in June 1795 and was short-lived.

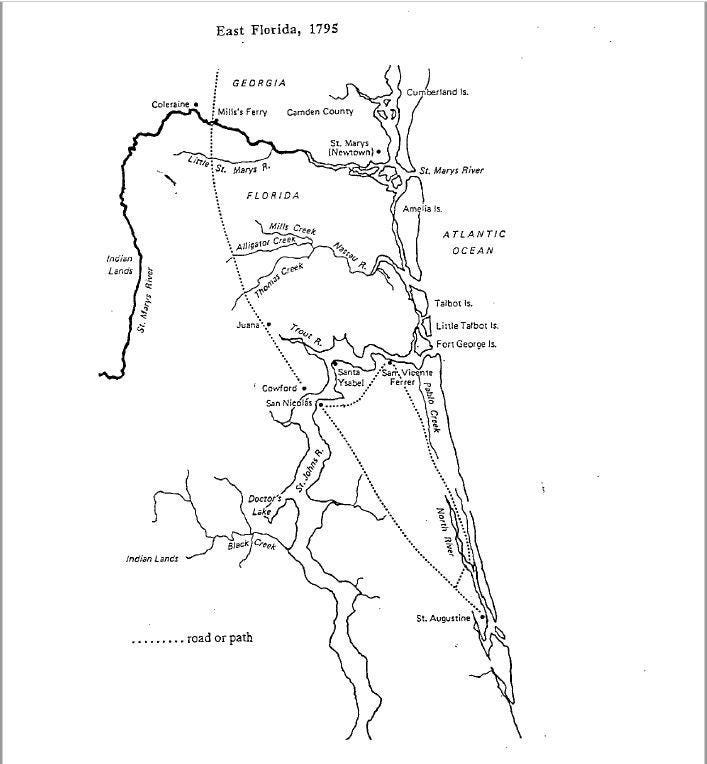

On 27 June 1795, Richard was at the head of an army of 72 men when they captured and burned Fort Juana, a northern outpost in East Florida.

About 2 weeks later he united his force with a hundred additional men including John McIntosh, John Peter Wagnon, William Plowden and William Jones. They attacked Fort San Nicolas which guarded the ferry station on the St Johns River, taking the Fort by surprise and capturing the entire garrison. This was followed by the seizure of Amelia Island3.

During the capture of Fort San Nicolas, some of those captured were forced, against their will, to sign an oath of loyalty to the rebels. This included Timothy Hollingswood, Joseph Summerlin and Daniel Hogan4, Nathaniel Hall, George Cook, and John Creighton5.

When Governor de Quesada received news of these attacks, he already had evidence that identified, beyond doubt, the involvement of Richard Lang. Richard had already admitted in writing that he was acting as the Commander of all rebel forces along the St. Marys River6.

In the face of Spanish reinforcements, the rebels had to retreat to the stronghold on Amelia Island. Some were captured. Those who weren’t captured hastened across the border to Georgia. The rebellion was over. The rebels may have been more successful had the settlers in East Florida better supported Richard Lang's occupying force7.

A Bit of a ‘Witch-Hunt’

The Spanish authorities made every effort to find and punish the rebels. In fact, this turned into a bit of a ‘witch-hunt’ with even those who had been loyal to the Spanish regime, such as Timothy Hollingsworth, ending up amongst the accused8.

There was also, an element of people informing on others in an attempt to save themselves. In Timothy Hollingsworth’s case, some may have seen an opportunity to ‘get back’ at him for the work he had done in the service of the Spanish authorities in the past while also trying to save themselves9.

It is hard to know how many of those who were brought into custody for their alleged involvement in the rebellion were actually guilty. Without doubt some were falsely accused. Perhaps, in some cases, as American immigrants, they were by association assumed likely involved. Also, as already mentioned, some, such as Timothy Hollingsworth had signed an oath of loyalty to the rebels under duress. This may have been used against them in court.

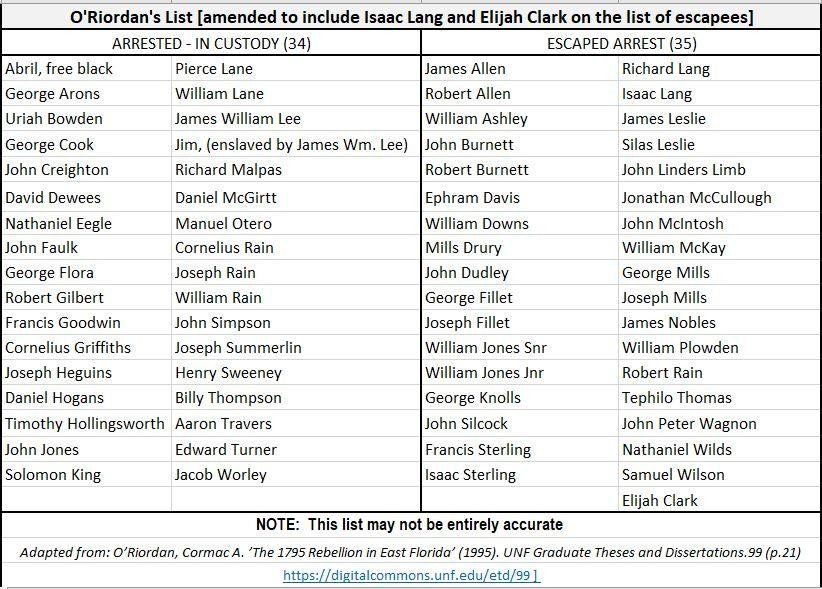

The precise number of accused and, of these, number in custody and number who escaped isn’t entirely clear:

Bennett10 writes that there were: 68 accused; 35 escaped; 33 in custody and

specifically mentions Richard Lang, Elijah Clark, John McIntosh, John Peter Wagnon and Richard’s son Isaac amongst those who escaped. He says that Richard and Isaac, along with others who escaped, were declared ‘rebels but not captured’.

O’Riordan11 says that there were 67 accused; 33 escaped; 34 in custody but omits Isaac Lang and Elijah Clark on the list of those who escaped arrest

What follows is O’Riordan’s list but with the addition, by me, of Isaac Lang and Elijah Clark. I am uncertain how accurate it is:

Tried in Absentia

The trial began in January 1796 and lasted for two years. Before and during the trial, the prisoners were confined in the Castillo de San Marcos, their health suffering as a result of the damp and dark condition of their cells. Before the two-year trial ended, Daniel Hogans, Richard Malpas, Solomon King, and George Arons had died in prison and Francis Goodwin went insane and had to be moved to the Royal Hospital12. Those who had escaped were tried in absentia.

Punishment

On 22 February 1798, sentences were handed down by Governor Enrique White [Governor of the Spanish Province of East Florida from June 1796 - March 1811]. Governor White, who had succeeded Governor de Quesada, imposed harsh sentences as a warning to others of the consequences of treason.

All of those who had fled, including Richard Lang, were sentenced to death in absentia. If captured, they were to be:

'taken to the Castillo de San Marcos, in this city, from where they will be taken by force and a rope will be placed around the neck of each one and they will be pulled by the tail of a horse, their crimes being announced by a crier who will walk in front of them, to the square, where they will be hanged from the gibbet by the executioner, and no one will impede the process or say that the sentence is too harsh. They will hang there until three o'clock in the afternoon when the executioner will publicly sever their heads and arms for the purpose of displaying them at the Post at San Nicolas'13

.

In addition, all of their goods were to be confiscated and their children were to be declared ineligible to claim any inheritance or to be accorded any dignity or public office14.

An alternative account suggests that, once hanged, their bodies were to be quartered before their heads and arms were erected in the vicinity of San Nicolas and the pass of the St. Johns15.

Of those who were prisoners in custody, Timothy Hollingsworth, who was most certainly innocent, William Lane, and James William Lee received the same death sentences as those who had escaped capture16.

The rest of the prisoners received lesser sentences17:

Fifteen were condemned to ten years of hard labour working on the fortifications of Havana, Pensacola, or St. Augustine. These were: William and Cornelius Rain, Edward Turner, John Jones, and Daniel McGirtt (Havana); David Dewes, Uriah Bowden, Aaron Travers, John Faulk, and Jacob Worley (Pensacola); and George Flora, John Simpson, Billy Thompson, Cornelius Griffith, and Henry Sweeney (St Augustine).

Nine were discharged because there was not enough evidence to convict them. They were: Joseph Summerlin, George Cook, John Creighton, Robert Gilbert, Joseph Heguins, Nathaniel Eegle, Manuel Otero, Abril (a free black), and Jim (the enslaved person of James William Lee). All nine, with the exception of Jim, were ordered to leave East Florida within fifteen days unless they relocated south of St. Augustine where they would be given land grants equal to the land they had held north of the St. Johns River prior to the rebellion.

One, Frances Goodwin, who had become insane during the trial was advised of his release at the Royal Hospital where he was confined.

In the end, the sentences of Hollingsworth, Lane and Lee were not carried out. Instead they received short jail sentences and had their property returned on release18.

Not all of those who fled to Georgia after the rebellion had their lands in East Florida confiscated or their children disinherited. Though their property was automatically forfeited to the Crown and, if nobody in the province applied to settle the land, then it was often re-granted to the former rebel owner19.

Richard was given permission to sell the land he had held in the province at the time of the rebellion. His Florida plantation, 'Casa Blanca', was sold to his friend William Drummond for $5000 in 181720.

Richard did not return to live in East Florida, although he did visit there on at least one occasion. More about that in Part #7 …

This post draws information from my family history archive on the WeAre.xyz platform.

Testimony of the 1795 rebels, bnd. 293P13 EFP cited O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 (p.18) via University of North Florida Digital Commons. Accessed 23 May 2022.

Extract from: Privateers in Charleston 1793-1796, Ch.5 Jay's Treaty via Ancestry.com. Privateers in Charleston, 1793-1796 [database on-line]. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Accessed 20 February 2020.

Cusick, James G. (2011). Some Thoughts on Spanish East and West Florida as Borderlands ''The Florida Historical Quarterly', 90(2), 133-156. via JSTOR [Website]. Accessed 24 May 2022.

Testimony of the 1795 rebels. First Declaration of Timothy Hollingsworth, July 20, 1795; First Declaration of Joseph Summerlin, July 18, 1795; First Declaration of Daniel Hogan, July 20, 1795, bnd. 293P12 EFP cited by O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 (p.11) via University of North Florida Digital Commons. Accessed 23 May 2022.

Testimony of the 1795 rebels. First Declaration of Nathaniel Hall, July 19, 1795, bnd. 293P12 EFP - cited by O’Riordan., Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida (p.12) - See Note 4.

Murdoch, Richard K. (1951) The Georgia-Florida Frontier 1793-1796. Spanish Reaction to French Intrigue and American Designs University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles (p.158).

Cusick, James G. (2011). Some Thoughts on Spanish East and West Florida as Borderlands ''The Florida Historical Quarterly', 90(2), 133-156. via JSTOR [Website]. Accessed 24 May 2022.

Murdoch, Richard K. (1951), pp.105-113 - cited by O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons. Accessed 23 May 2022.

O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons (p.17) Accessed 23 May 2022.

Extracts from: Bennett, Charles E. (1981) Florida's "French" Revolution 1793-1795. Gainesville: University of Florida Press) in document Florida's French Revolution via Ancestry.com (shared by Ralan64 on 19 May 2013). Accessed 24 May 2022.

Murdoch, Richard K. (1951), pp.105-113 - cited by O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons (p.14). Accessed 23 May 2022.

Final Sentencing of the 1795 rebels, bnd. 294P12 EFP cited O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons. Accessed 23 May 2022 (p.15).

Final Sentencing of the 1795 rebels, bnd. 294P12 EFP cited O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) - See Note 12.

O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons. Accessed 23 May 2022 (p.16)

Extracts from: Bennett, Charles E. (1981) Florida's "French" Revolution 1793-1795. Gainesville: University of Florida Press) in document 'Florida's French Revolution' via Ancestry.com (shared by Ralan64 on 19 May 2013). Accessed 24 May 2022.

Final Sentencing of the 1795 rebels, bnd. 294P12 EFP cited O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons. Accessed 23 May 2022.

Final Sentencing of the 1795 rebels, bnd. 294P12 EFP cited O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) - See Note 16.

O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons (p.19). Accessed 23 May 2022.

O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) - See Note 18.

Spanish Land Grants in Florida, III:D21 cited in O’Riordan, Cormac A. (1995) The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida. UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 99 via University of North Florida Digital Commons (Chapter 1, footnote 42).

I’m not at all surprised that Richard decided not to return to East Florida. That death sentence was dreadful to read. I’ve never heard of the East Florida Rebellion so thanks for the opportunity to learn a little more about American history.