This post is an updated version of a guest post I wrote for The DNA Geek in 20221. I am reposting it here in slightly modified form because the original post now contains broken links and out-dated material.

DNA is an important addition to any genealogist’s toolbox because it adds to the body of evidence, allows us to interrogate our paper trail, and provides clues to better investigate our brick walls. However, for those of us who start with no personal documentation at all, DNA evidence is critical, and the DNA journey is a deeply personal path of discovery.

I speak from personal experience. I was born in England to a British mother and an American serviceman. After DNA testing in 2013, I was able to identify who my biological father is. He had died several years before I ‘found’ him. I have some—limited and tenuous—contact with my American family.

As a ‘War Babe’ within the terms of the War Babes settlement, I was able to access relevant information from the National Personnel Records Centre (NPRC) in St Louis.

The War Babes Settlement

In the 1980’s, two British organizations formed to support British adults who had been born to American servicemen during World War II and who wanted to find their GI fathers: TRACE (Trans-Atlantic Children’s Enterprise); and the War Babes organization. At the time, the NPRC argued that the US Privacy Act prevented them from releasing information about the veterans.

In 1989, the War Babes organization sued the US government. Amongst other things, their Washington based lawyer, Joan S. Meier, argued that the separation of ‘war babes’ from their fathers was often the result of US military policy that “encouraged men to have a good time” then “whisked them away so that they could not be found”2.

The 1990 War Babes Settlement was the outcome of that action. The Settlement balanced the US Freedom of Information Act with the privacy law in such cases. The agreement outlines how ‘war babes’ can request information from the NPRC and what the NPRC can divulge. If the GI being sought is still alive, the information includes the city, state, and date of each address on file. Also, if requested, the NPRC will forward a letter on the applicant’s behalf to their father by certified mail, return receipt requested. If the GI is deceased, the entire address is given.

While the class action was initially focused on those born in Britain during World War II, the provisions of the War Babes agreement signed in 1990 are more generally applied to anyone who was conceived and born somewhere other than the USA and whose biological father is/was a US serviceman who was there on military assignment at the time or, as the National Archives puts it: "foreign children of American servicemen who served overseas...and fathered children during their service abroad."3

DNA Can Cut Through Red Tape

Over the years, tens of thousands of babies have been left behind, estranged from their biological fathers and their American heritage. For those looking for their GI fathers, autosomal DNA testing has made a huge difference. That is not to say that people didn’t find their GI fathers prior to the advent of genetic genealogy. Some did, but the search was often very long, tedious, and frustrating. For others, it was impossible. Prior to 1990, even once a likely father was identified, their child was unable to get confirmation or contact information from the NPRC.

As with any unknown parentage puzzle, finding the answer requires combining DNA evidence with more traditional documentation, including the likelihood that any potential father was in the right place at the right time. For ‘war babes’, the 1990 agreement is significant because it can sometimes provide that final confirmation of the father’s location at the time of conception, as well as his current city of residence.

Because of my interest, I belong to a number of forums where ‘war babes’ seek help. Occasionally, in the past when I have had the time, I have offered my help. People seek help at various stages of their quest. Some have yet to DNA test. Sometimes people have DNA results but are at a loss as to what to do with them. At the other extreme are those who have done the DNA work themselves and are seeking a second pair of eyes to confirm that they are on the right track or have identified the right person.

My expertise is pretty much limited to what I have learned from working with DNA myself and from tuning into relevant forums, webinars, blog posts, etc., along the way. I don’t have a scientific background. I am very reliant on the fabulous tools and explanations that people who have a deeper knowledge provide. As a mostly self-taught volunteer, when I was working these cases, I usually operated on the principle that it is better to support people to understand and work with their DNA results themselves than simply to provide an answer for them. I have learned so much by working with the data.

Janet

“Janet” grew up as an adoptee. (“Janet” has given her permission for her story to be shared. All names have been changed for privacy.) When I ‘met’ her online, she was 75 years old and had already tested with AncestryDNA4. She was in contact with a family member via Ancestry messaging and had done some work herself to pull all the information she had together. Her focus was on several DNA matches predicted to be 1st to 3rd cousins. She had gradually narrowed down her search to four brothers: Ernest, Hugh, Oscar, and Leonard, all deceased.

After considering documentary evidence and information from the family, Janet concluded that three of the four brothers were either too young and/or would not have been in England at the time in question. That left Ernest. After Janet consulted her family contact, Ernest’s sister Olive was approached to see if she was willing to DNA test. At the time, Olive was 97 years old and the only one of the siblings still living. Ernest had died in 2002.

Given the speed at which things were going with family, Janet wanted some reassurance that she had drawn the right conclusions so that she could more confidently engage with family. She was also wondering what she might expect to see in her results if Olive did agree to test. At this point (June 2021), Janet posted online, and I began to help her.

My first priority was to review her work so that I could either reassure her that it was likely correct and explain why, or steer her in another direction if needed.

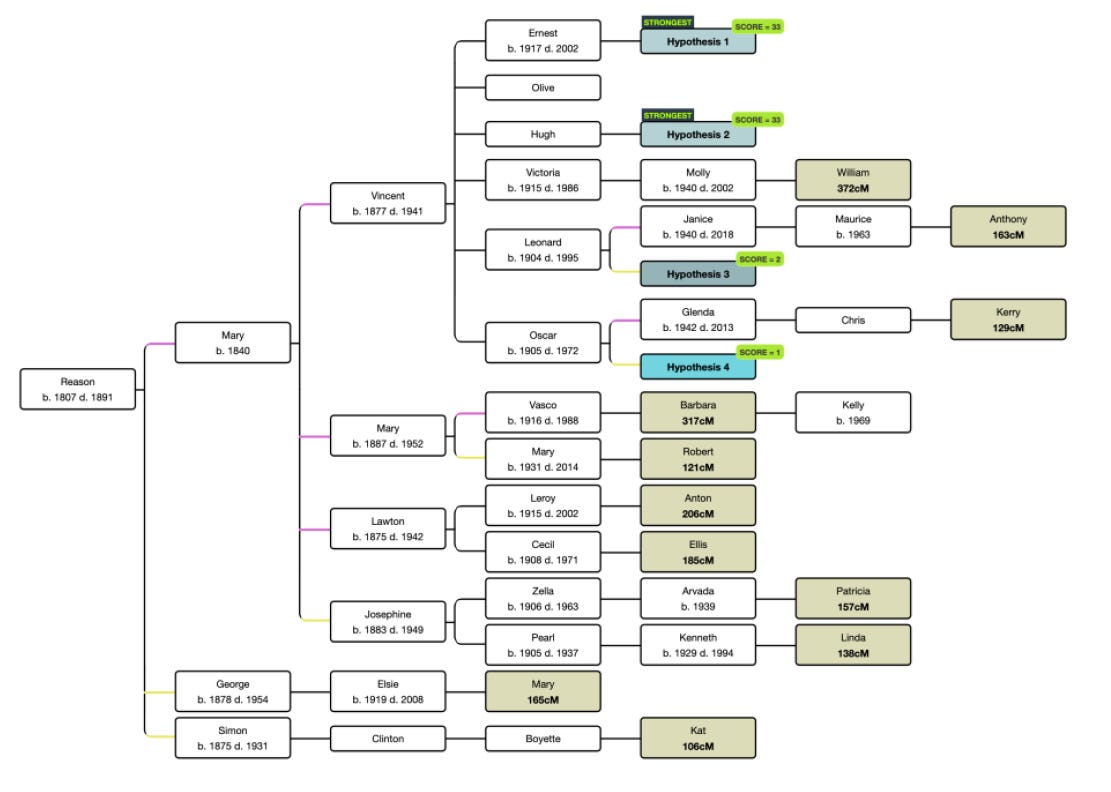

I reviewed Janet’s match list and built a What Are The Odds (WATO) tree at DNA Painter5 using DNA matches who shared from 106 centimorgans to 372 centimorgans (cM) of DNA with Janet.

[The amount of DNA shared between DNA matches is usually shown as a centimorgan (cM) value. A centimorgan is a unit of measure for the frequency of genetic recombination6].

Using WATO helped me to visualize the relationship probabilities and made it easier to explain to Janet what her results were saying. I wanted to have confidence in the result.

The WATO tool generates hypotheses based on DNA matches, but not all are realistic for contextual reasons, like gender or age. After removing some hypotheses it was clear that, of the prospective fathers left, the most probable were Ernest and Hugh, two of the brothers Janet had identified. Leonard was also possible but less likely than his brothers and, in any event, we knew him to be too young. The fourth brother could not have been Janet’s father according to WATO. Again, we knew he was too young anyway.

At this stage, Janet could have written to the NPRC under the War Babes agreement and requested the records for both Ernest and Hugh. She didn’t because, at the time (2021), the office was temporarily closed as a result of Covid19. These records may have confirmed that Ernest was in England at the time and that Hugh was not. Fortunately for Janet, it wasn’t entirely necessary because her family was confident that Hugh had not been in England during the War while Ernest had been. Ernest was in England in 1944 and 1945 to recover from injuries. Janet was born in 1946 so the timing worked. At this point, it seemed that Janet’s conclusion that Ernest was her father was correct.

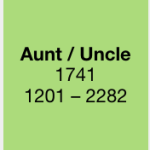

As things turned out, Olive was more than happy to DNA test for Janet. She was just as eager to know the outcome. To help Janet understand what she might expect to see when Olive’s results came through, I drew her attention to the Shared cM Project tool, also at DNA Painter7. Ernest and Olive are full siblings, so if Ernest was Janet’s father, Olive is her aunt. The tool indicates that an aunt–niece relationship is likely to share between 1201–2282 cM of DNA with an average of 1741 cM.

When Olive did appear on Janet’s match list, she shared 1835 cM, well within the expected range and slightly more than the average amount expected for her to be Janet’s Aunt. That amount could, of course, also indicate other relationships, like grandparent–grandchild, half sibling, or niece, in addition to aunt. However, those other possibilities could be excluded by context.

By this time, the family had become quite excited at the prospect of Janet being Ernest’s daughter. She was told that Ernest and his wife could not have children together and that he would likely have welcomed her with open arms.

Soon there were voice and video calls across the Atlantic between Janet and her family. This was followed by a trip to Florida to visit her aunt. Other members of her family flew into Florida from other parts of the US to meet her as well. Janet now has pictures of her father and other family members and remains in regular contact with her American family.

Not all Experiences Are the Same

I chose Janet’s story because it was a relatively easy search that ended with a successful connection to family. All roads seemed to point to Ernest, and it was a bonus when Olive tested to add further weight to this. However, for many people it is not so straightforward.

Some searches are much more protracted. They entail either a waiting game for closer DNA matches to pop up or a careful and sensitive attempt to get potential family members to DNA test. With time and persistence, these searches too can be successful.

For others, the challenge is getting documentary evidence to sit alongside their DNA results. Some much needed information is not available from the NPRC because the records were lost in the fire there on 12 July 1973. Approximately 16-18 million Official Military Personnel Files were lost in that fire8.

Not everyone gets a positive response from family like Janet did. While some people are content to know who their GI father is without need for contact, others want to build a relationship. Relationships are two-way things. We can’t expect them as a right. They require willing and active engagement from both sides. Sometimes, for a whole variety of reasons, that just doesn’t happen.

Everyone’s experience is different. For this reason, it can be scary commencing a search for a GI father. There is uncertainty about what will be found and about what reaction there will be if contact is made with family. However, if you don’t try, you will never know. In my view, it is a chance worth taking.

Where to Get Help

The following resources were set up specifically for the benefit of people who are trying to trace their American GI fathers, grandfathers, or other family members. They offer support, help, and information free of charge, including information about how to apply to the NPRC under the War Babes agreement:

The GI TRACE website has a lot of information and includes links to: A Forum and to an associated private Facebook group where you can seek help9.

The Find My GI Father private Facebook group provides information and support10.

Jane Chapman - Guest Post ‘War Babes’ - posted 25 March 2022 - The DNA Geek [Wordpress Blog by Leah Larkin] - https://thednageek.com/war-babes/

Tampa Bay Times ‘War babies get help finding dads’ - Published Nov. 20, 1990|Updated Oct. 18, 2005 - https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1990/11/20/war-babies-get-help-finding-dads/

See also: Deseret News, The Washington Post' ‘Britons to get locations of es-GIs who may be Dads’ Published: Nov 18, 1990, 12:00 a.m. MST - https://www.deseret.com/1990/11/18/18891724/britons-to-get-locations-of-ex-gis-who-may-be-dads/

‘War Babe Requests’ National Archives - https://www.archives.gov/veterans/military-service-records/war-babe-requests

AncestryDNA - https://www.ancestry.com/dna/

What are the Odds (WATO) - https://dnapainter.com/tools/probability

[These days, I would be more likely to use WATO Plus - https://dnapainter.com/help/user-guide/wato-plus. However, I was working with Janet during 2021. WATO Plus didn’t become available until 2024. The original WATO remains a very good tool to use. You can read about the differences between WATO and WATO Plus here - https://dnapainter.com/blog/wato-vs-wato-plus/ ]

Glossary - National Human Genome Research Institute - https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Centimorgan-cM

Shared cM Project Tool at DNA Painter - https://dnapainter.com/tools/sharedcmv4

[If you are working with DNA for family history purposes, DNA Painter has lots of useful features to use, in addition to those mentioned in this post - https://dnapainter.com/

This figure comes from ‘NPRC’ on the Gi Trace website - https://gitrace.org/nprc

GI Trace - Explore all the Tabs at: https://gitrace.org/

GI Trace Forum - https://gitrace.org/social-media

GI Trace Facebook Group (private) - https://www.facebook.com/groups/gitrace.org/

Find My GI Father Facebook Group (private) - https://www.facebook.com/groups/FindMyGIFather

Thank you for doing this work. I did not anything about these people or that there were organizations to help them find their families. thank you for sharing!

Fascinating. I had no idea that these organizations existed. I love learning things like this. Thanks for sharing!